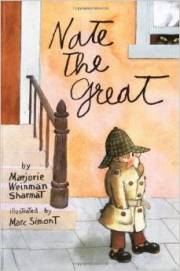

Nate the Great (image from amazon.com)

I love detective stories. Not modern detectives (too much blood and guts for me), but old-fashioned, tough talking detectives, those stylishly dressed men who trade quips with clever dames. I make no apologies for my literary crush on Archie Goodwin. So, with a long list of literary detectives on the children’s shelf, which is the best option to start kids on a lifetime of appreciation for snappy comebacks in the midst of nifty crime solving?

My best candidate: that classic crime-solver, Nate the Great.

If you haven’t reread Nate the Great since you grew up and encountered his adult counterparts, you might be surprised to see all the ways Nate is the perfect training ground for future gumshoe fans.

- His tough but quirky persona. Nate is a tough guy. Not unfriendly, but business-like … as one has to be in the crime solving game. You can see it in his introduction of himself in his very first story (called, not surprisingly, Nate the Great): “My name is Nate the Great. I am a detective. I work alone.” Even when talking to a client, he’s a cut-to-the-chase kind of kid: “’Stay right where you are. Don’t touch anything. DON’T MOVE!’ ‘My foot itches,’ Annie said. ‘Scratch it,’ I said.” This is the kind of no nonsense talk that should inspire confidence in clients (even if Annie has to ask him, “Are you sure you’re a detective?”). Along with a tough exterior, every detective needs those little touches that set him apart, that become a signature of his style. In that first story we encounter Nate’s “detective suit” (trench coat and official looking hat), his love of pancakes, and his admirable habit of leaving a note for his mother, typically in cursive, when he goes out on a case: “Dear mother, I will be back. I am wearing my rubbers. Love, Nate the Great.”

- His kooky sidekicks. In the first book of the Nate the Great series, we meet two girls who will stick with Nate through many of his later books. His first client is Annie, an African-American little girl with a giant dog named Fang. Nate explains that Annie “smiles a lot,” adding “I would like Annie if I liked girls.” We also meet Annie’s friend, Rosamond. I would venture to guess that Rosamond was the first Goth girl most of us met through literature. Seriously. She has long black hair, green eyes, and she’s “covered with cat hair.” She also has four black cats: Big Hex, Little Hex, Plain Hex, and Super Hex. Perhaps my favorite out of all the charming illustrations in Nate the Great is the picture of Rosamond’s room and her many, many pictures of black cats, each done in a different pop-art style. These friends not only fit into the mold of a classic detective story, they manage to be diverse and interesting in a way that’s refreshingly casual. All too often characters in children’s books are saddled with a set of friends who seem self-consciously unique, as if the author felt the need to announce, “Look at these DIVERSE and UNIQUE characters!!” Nate’s girls are different in a way that seems organic to the story.

- His child-sized mysteries. So, there’s a bit of a central problem with mysteries for kids. A mystery needs a crime … but the idea of kids grappling with crimes on their own quickly becomes uncomfortable. I mean, I’m thrilled that you found that diamond necklace, Cam Jansen, but isn’t it time to, you know … call the police already? The mysteries in Nate the Great are the kinds of “crimes” that kids encounter every day. Adults may consider them to be just inconveniences, but kids know the truth. Trust me. In my classroom, I have had some version of this conversation too many times to count:

Child: Someone stole my _____________ (boots, pencil, spelling folder)!

Me: Really? Are you sure someone actually stole it?

Child: Well, it’s not here, is it?

Me: So you mean your ______________ is missing, right?

Child: That’s what I said! Someone stole it!

There is no point in trying to argue the logic of what a dastardly thief would do with someone else’s spelling folder … the crime is clearly defined. Those kinds of mysteries of inconvenience are exactly what Nate takes on. He may be a little personally disappointed by the size of those crimes – in the first story he is hoping for a call to look for “lost diamonds or pearls or a million dollars” – but he’s nevertheless willing to investigate them. The solutions are always satisfying, too, typically requiring the characters to look more closely at something already in plain sight.

- His hard-boiled tone. Writing a book for early readers is not easy. I can only imagine that, as an author, it can feel like a constant set of restrictions: you don’t want to use a word that’s too big or a sentence that’s too long, so you’re forced to fit your story into the box of those limitations. There are a very, very few authors who manage to make those limitations an asset to the story. Mo Willems does it with his Elephant and Piggie stories. Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad stories are poetic in their simplicity. Dr. Seuss was a master of it. And to those names, I would add Marjorie Weinman Sharmat with her Nate the Great stories. These are technically “early reader” books – they would be considered to be at an end of first grade or beginning of second grade level, typically – but all those features that make them easier to read don’t feel artificial to the story. On the contrary: the short

Nate the Great and the Pillowcase (image from amazon.com)

sentences, simple vocabulary, line breaks, and repetition just feel like the way any hard-boiled detective would talk. Take this dramatic moment when Nate meets Annie’s dog, Fang: “Fang was there. He was big, all right. And he had big teeth. He showed them to me. I showed him mine. He sniffed me. I sniffed him back. And we were friends.” The conventions of early reader children’s literature dovetail so perfectly with the conventions of detective stories that they don’t feel like restrictions as much as an artistic choice by the author.

If you’re looking for a story to grab your early readers, to provide them with a genuinely engaging plot and characters, look no farther than Nate the Great. And if you’re an adult fan of the genre, do yourself a favor: put on your detective suit, make yourself a plate of pancakes, and revisit this little detective.